CORCORAN, Calif. —

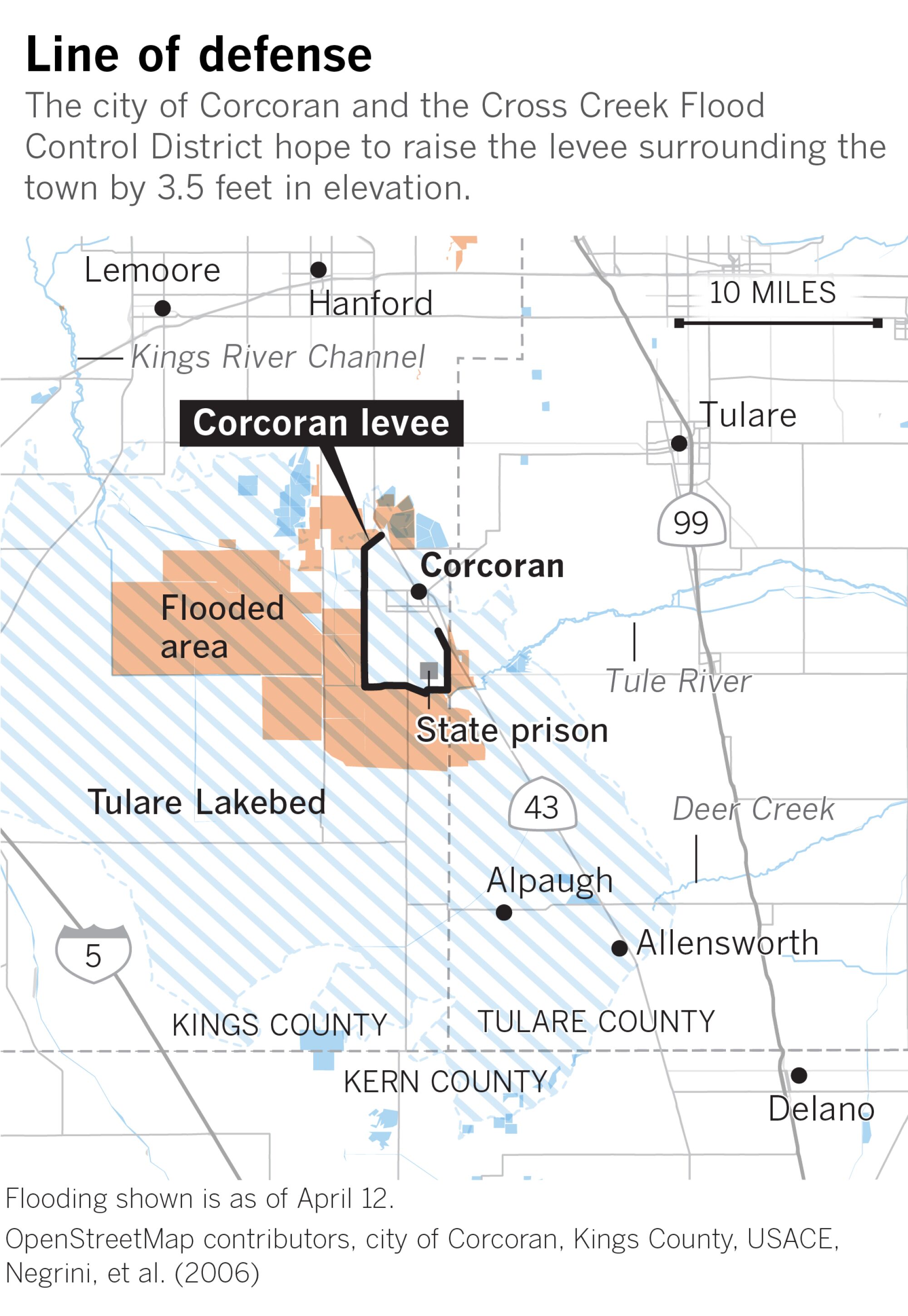

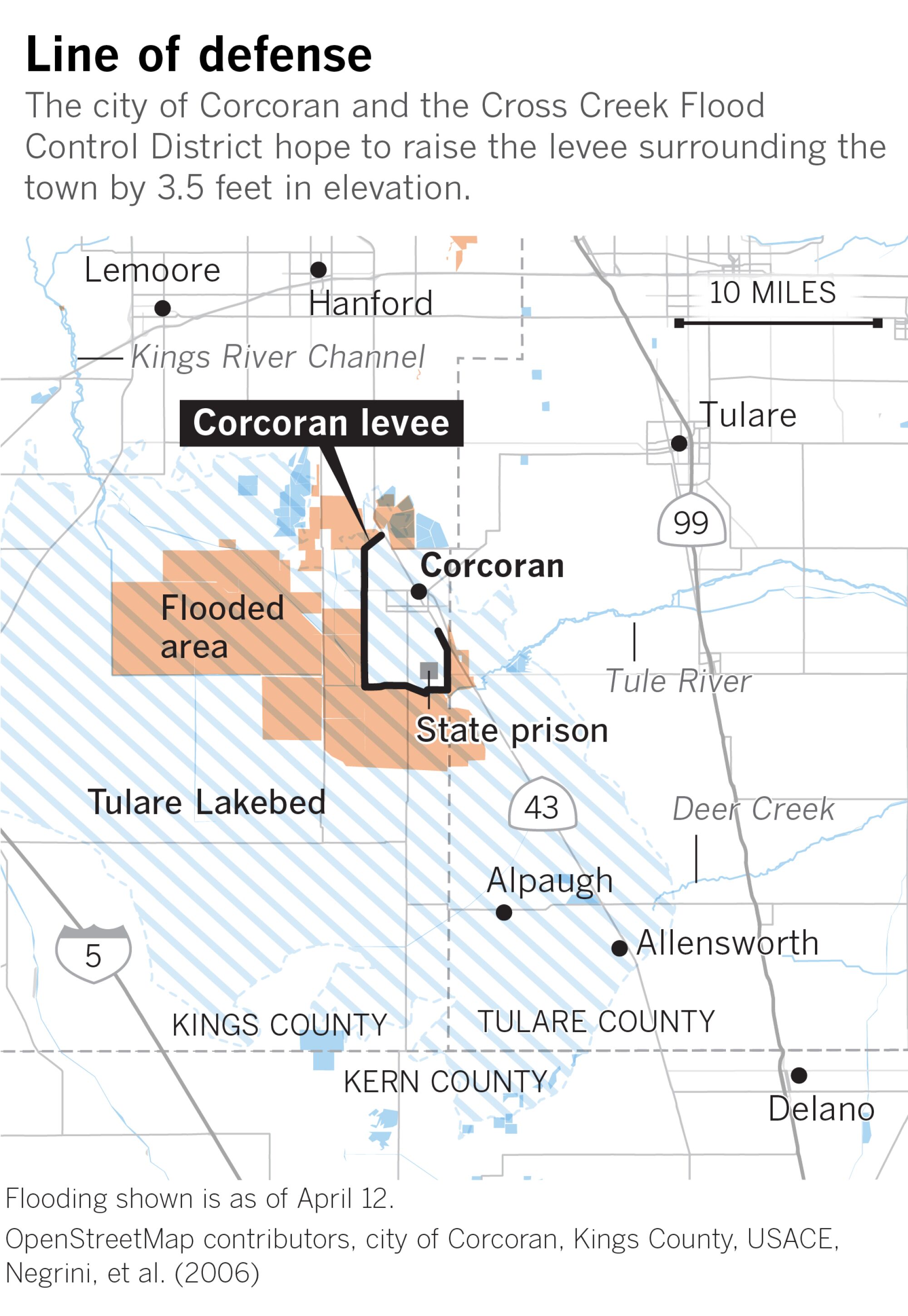

Just west of this normally dusty prison town, a civic nightmare is unfolding: Tulare Lake, a body of water that did not exist just two months ago, now stretches to the horizon — a vast, murky sea in which the tops of telephone poles can be seen stretching eerily into the distance.

Anxious residents in this Central Valley city of 22,000 know all too well that the only thing keeping this growing lake from inundating their homes and businesses — as well as one of the state’s largest and most crowded prison complexes — is a 14.5-mile-long dirt levee that rises up from sodden earth to the west, south and east.

And that levee, according to city officials and local farmers, could be in big trouble.

They worry that this nondescript earthwork may be too low to hold back the millions of gallons of melted snow that are expected to course into the Tulare Lake Basin as summer sunshine warms the slopes of the Sierra Nevada. They worry even more that with water sloshing against the levee for up to two years, it may start to erode and breach.

Many here say they are perplexed and frightened that state and federal officials don’t seem to be taking the threat seriously, since the federal government has estimated that flooding would cause $6 billion worth of damage. They note that both California State Prison, Corcoran, and the California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility — a dual prison complex that holds about 8,000 incarcerated men and employs many local residents — stand in the path of potential destruction.

“Nobody has ever seen that much snow,” said Jason Mustain, a clerk at the Corcoran hardware store and a former firefighter. “Of course I’m stressed.”

Mustain is not alone.

A bottle of Tums antacid tablets rattled in the cup holder of Kirk Gilkey’s truck recently as he drove around the area surveying the rising water.

Gilkey’s family has been farming in the area for generations. He said this is the first year in decades that his farm won’t plant cotton because of flooding. But what distresses him most is not the financial pain big farmers will experience but the hardship that will be visited upon workers and their families who are dependent upon agriculture for their livelihoods.

“People are scared,” he said. If “Corcoran floods, it’ll be a ghost town after. It won’t survive.”

City Manager Greg Gatzka, who for weeks has been waging an unsuccessful campaign to marshal state and federal funds to bolster the levee, said he is “beyond frustrated” by the difficulty of accessing emergency funding.

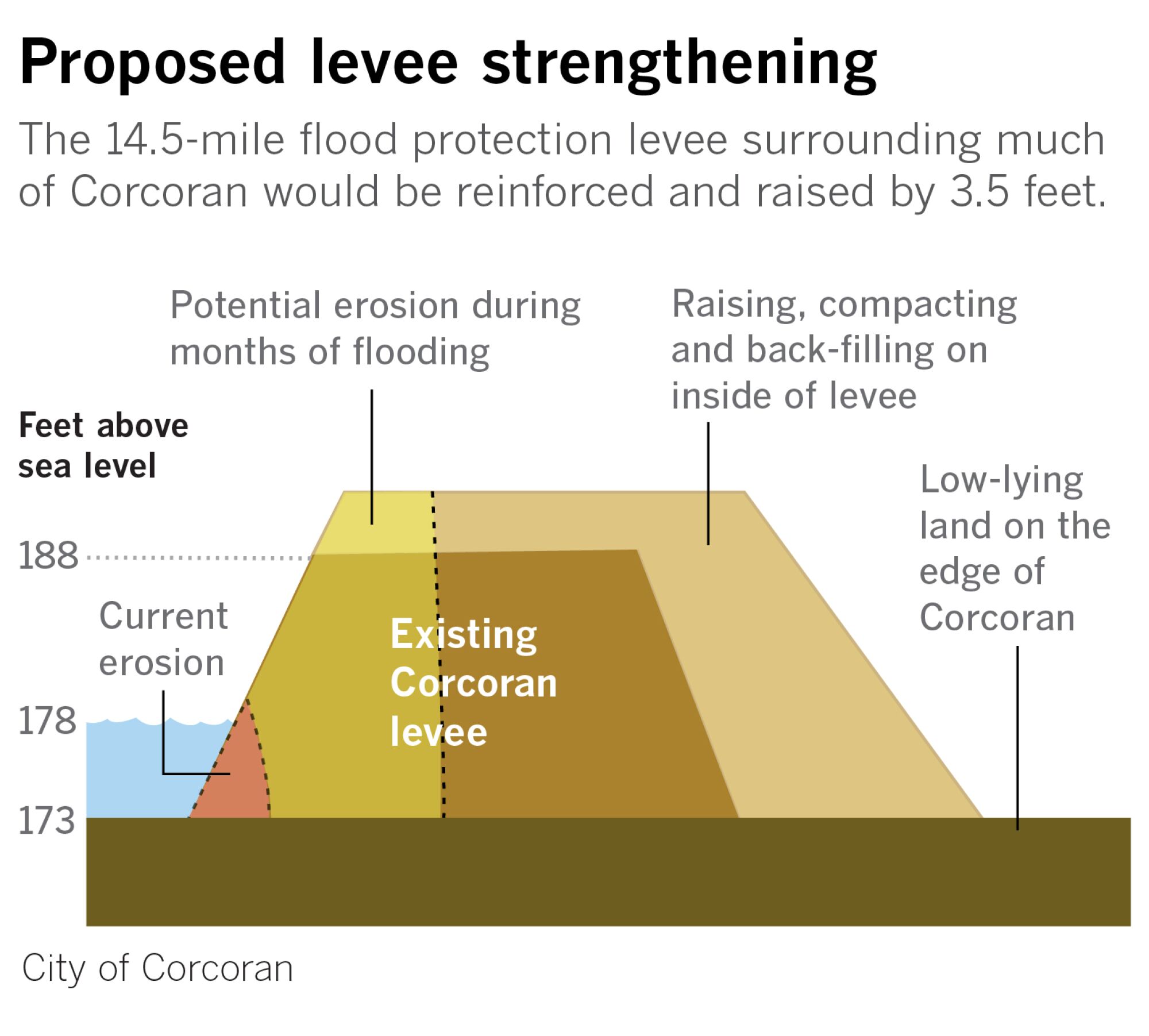

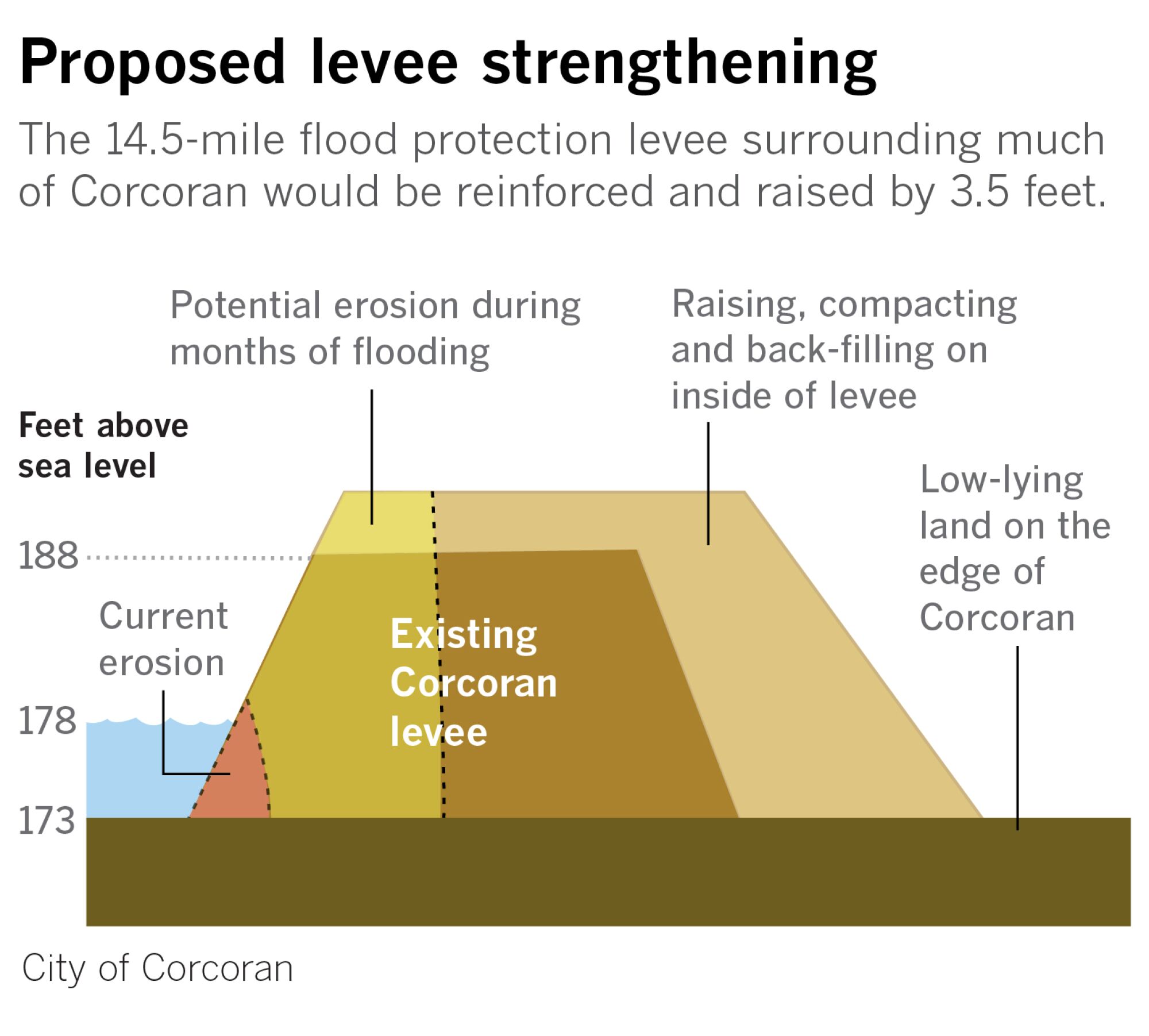

Local officials want to see the levee reinforced and raised by 3.5 feet — an engineering feat that would cost $21 million, according to Gatzka.

In the meantime, the Cross Creek Flood Control District, which is responsible for the levee, has tapped reserve funds to begin gathering dirt to reinforce it. But Gatzka said the agency has exhausted its resources and needs state help.

As a “desperate last resort,” Gatzka said, the agency may also ask local farmers — including Pasadena-based cotton-growing giant J.G. Boswell Co. — to make donations to support the work.

Officials at Boswell and the Cross Creek Flood Control District did not respond to a request for comment.

“My biggest fear,” Gatzka said, is that the levee will “become compromised through erosion or deterioration, and then water is going to be heading toward the city, and we will have to be looking at evacuation.”

He said the city has heard that state and federal officials are “working on” assistance for the levee, “but it needs to come faster.”

For their part, officials at several state and federal agencies said they are monitoring the situation closely but referred questions — and responsibility — back to local officials.

The Army Corps of Engineers, which helped shore up the levees around Corcoran in 1969 and 1983, said Tulare Lake and the Corcoran levee system do not “fall under [Army Corps] authority.”

Officials with the state Department of Water Resources said its Flood Operations Center has deployed technical specialists to inspect the levee and is “conducting modeling and mapping to develop tools to assist with local decision making.”

Assemblyman Devon Mathis (R-Visalia) said in a statement that the city is “working with private entities to secure funding for levee repairs.” He added that his office is trying to secure additional funding.

State Sen. Melissa Hurtado (D-Sanger) said her office has been in “frequent contact” with state and local officials and farmers to “ensure strategic action has been taken.” She added, “We are continuing to monitor this situation and will continue to work to facilitate conversations between state, local and federal partners to ensure the community of Corcoran is safe from potential flood impacts.”

But as the days grow longer and warmer, people in Corcoran and elsewhere in the region are increasingly worried that not enough is being done to prevent catastrophic flooding.

City officials, in plea after plea, have laid out the stark math of their problem.

Parts of Corcoran are 174 feet above sea level. The water pooling just west of town has reached 178 feet — and could rise higher.

The levee’s current height is 188 feet.

The earthwork should be strong enough to hold back 1 million acre-feet of water, Gatzka said.

But what if more water than that comes coursing down from the mountains? The snowpack in the southern Sierra is estimated to be 300% of normal. And farmers upstream are not clamoring to siphon off as much water as they would in drier years. What’s more, the ground beneath Corcoran has sunk, the result of overpumping of water from aquifers that has caused the earth to become compressed — a phenomenon known as subsidence.

Adding to the uncertainty are questions about the integrity of the levee itself. Local officials worry that it will be unable to withstand the pressure of water sloshing against it for up to two years, which is how long it may take for Tulare Lake to recede. (A thick layer of clay underlies the Tulare Lake region, preventing floodwaters from percolating into aquifers.)

The threat of flooding is one the region has faced for decades. Corcoran is situated at the edge of what was once a giant lake — that is, until farms diverted the water from the Kings, Kaweah, Tule and Kern rivers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Corcoran was incorporated in 1914. Like many towns in the San Joaquin Valley, its founder was a real estate developer with dreams of making it rich. But many here regard J.G. Boswell as the city’s real founding father. His namesake company, among the largest agricultural interests in California, was established in Corcoran in 1921 and remains the town’s most influential employer.

The majority-Latino town — along with smaller hamlets scattered about the Tulare Lake Basin, such as Allensworth, Alpaugh and Stratford — has been threatened with flooding just about every time there is a monster snowpack in the Sierra.

In 1969 — a year so wet that a pair of ranchers and their sons set off on a boat trip through Tulare Lake all the way to San Francisco — the Army Corps of Engineers partnered with local officials to build levees to protect Corcoran. By April, the lake had reached 188 feet above sea level and was rising approximately 1 foot per week. The levees built that year were 192 feet high.

Some of those levees were removed once the water receded.

In 1983, another series of storms pounded the region. The Army Corps again came to the town’s rescue, constructing the current levee around Corcoran but extracting a promise that the Cross Creek Flood Control district would be responsible for maintaining it.

In 2015, the levee was raised after officials grew alarmed by increasing subsidence. Two years later, after a particularly wet winter, officials discovered that it had sunk by 2 feet. Roughly $14 million in Corcoran taxpayer dollars was spent to raise it once again.

Complicating matters is an additional bit of infrastructure in Corcoran: a massive prison complex run by the state of California.

The California Department of Corrections opened the Corcoran prison in 1988. Welcomed by local leaders as a potential economic boon, it was constructed on the south end of town. A decade later, the state opened the adjacent Substance Abuse Treatment Facility. Together, the two institutions house about 8,000 people on properties adjacent to the levee.

In Facebook groups for families of inmates, women with loved ones in the prison said fears about the levee’s integrity fill them with anxiety.

Meanwhile, around town, rumors abound that the prison is secretly evacuating prisoners in advance of flooding. A spokeswoman for the Department of Corrections said via email that there is no immediate danger and that no inmates have been evacuated. But, she added, the facility has stopped accepting new prisoners because of the situation.

Still, the potential for disaster has been a boon for at least one business in town: the Lake Bottom Brewery & Distillery on Whitley Avenue, the town’s main street. The wood-paneled watering hole has seen a flood of water tourists and journalists from around the country.